- Home

- Español

- Prices

- Signup DV

- Signup Parenting

- About

- Classes

- Resources

- Login

About Our Courses

Research Based, Evidence-Based Program and Curriculum

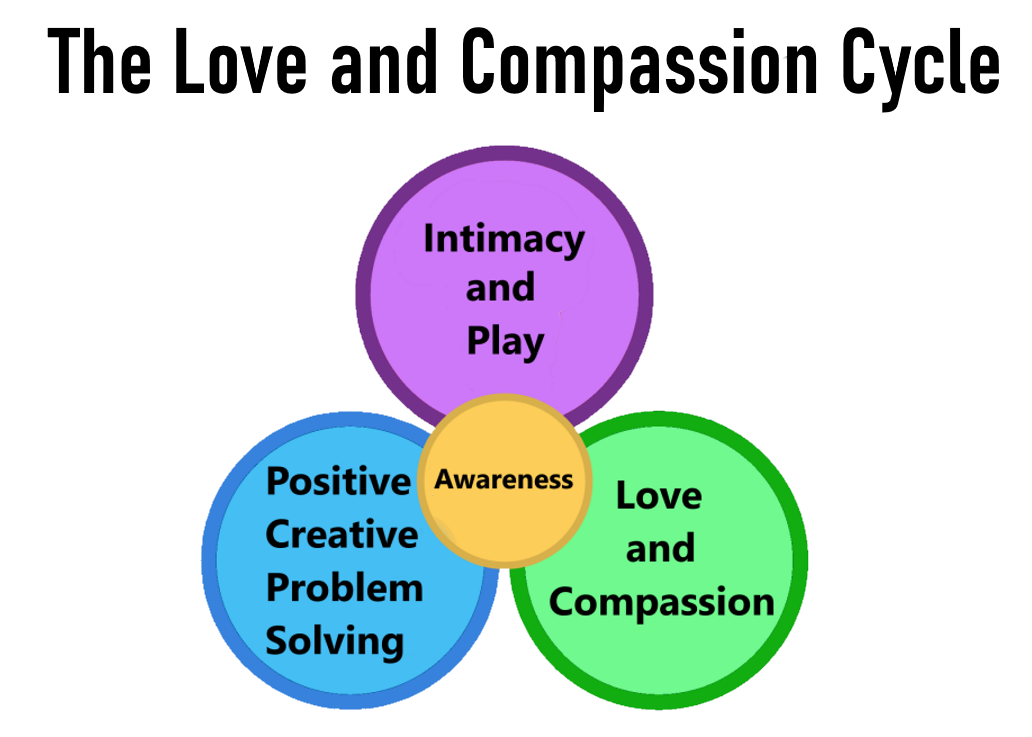

Streets2Schools uses the Research-Based Whole-Souled Success Programs and curriculums (Healy, 2020). The purpose of the Whole-Souled Success Programs and curriculums are (1) to eradicate Domestic Violence, (2) help clients self-regulate thoughts and emotions, and (3) eradicate child endangerment and abuse. The programs and curriculums assist participants through an interpersonal / cognitive behavioral approach to develop and master the concepts, skills, and strategies required to change thinking and behavioral patterns (Babcock, et al., 2004 & 2016) from the domestic violence cycle (Mason, 2021), anger-induced thinking and behavioral patterns, and cycles of poor parenting to the love and compassion cycle (Healy, 2020).

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE CYCLE → LOVE AND COMPASSION CYCLE

Presetting expectations

Expectations and norms are preset at the beginning of each program session. S2S reviews specific expectations and norms to set clear goals for the two-hour time together. This practice helps client’s avoid uncertainty and dysregulation when they intentionally or inadvertently digress from the expectations and norms and are reminded of these initial goals during feedback (Cho, & Cho, 2018).

Individualizing and Differentiating Program Curriculum While in a Group Setting

In each module of the Whole-Souled Success Program and curriculum specific techniques are presented in a scaffolded format. Scaffolding facilitates moving the client toward his/her potential cognitive understanding of the material (Wood et al. 1976). The aim of scaffolding is to support the transfer of responsibility for a task or learning from the facilitator to the client (Van de Pol et al. 2010).

The facilitator defines a concept, skill, or strategy and then provides examples of why, when, and how to apply the concepts, skills, and strategies presented. The facilitator then guides the participants in practicing the concepts, skills, and strategies by providing opportunity for independent application.

A participant’s acquisition of concepts, skills, and strategies requires:

- Explicit, incremental, sequential, and cumulative instruction

- Repeated practice of steps to develop automaticity

- Higher level skills rely on automaticity of lower-level skills

- Skills ultimately operate in the background without much conscious effort when imputed from short-term to long-term memory and general fund of knowledge.

A participant’s acquisition of learning involves (Bloom,1956):

- Knowing concepts, skills, and strategies

- Understanding concepts, skills, and strategies

- Applying concepts, skills, and strategies

- Synthesizing concepts, skills, and strategies

- Valuing concepts, skills, and strategies

When presenting concepts, skills, and strategies, assumptions about client’s ability cannot be made. Facilitators require a deep understanding when working with severely challenging clients because of behavior associated with domestic violence, dysregulation, neglect or abuse of children. There are societal implicit biases and a tendency to make unconscious assumptions about the violent, dysregulated offender. Our experiences inform the position that all too often clients fail to acquire the intended learning because of these biases and assumptions from those in the client’s circle of influence. The counter to implicit biases and assumption formation is quality professional training and an increase in love and compassion for the client.

Gradual Release Process - I Do, We Do, You Do

The gradual release of responsibility, also known as I Do, We Do, You Do, (Levy, 2007) is a teaching/ coaching strategy that includes demonstration, prompt, and practice. At the beginning of facilitation or when new material is being introduced, the facilitator has a prominent role in the delivery of the content. This is the “I do” phase. But as the participant acquires the new information and skills, the responsibility of learning shifts from facilitator-directed instruction to participant processing activities. In the “We do” phase of learning, the facilitator continues to model, question, prompt, and cue participant; but as the participant moves into the “You do” phases, they rely more on themselves and less on the facilitator to complete the required task.

The Facilitator Evaluation Scale©

The Facilitator Evaluation Scale© (Healy & Kelly, 2016) measures participants’ weekly progress in the subscale areas of attendance, participation, responsibility (acceptance), attitude (cognitive), and use of skills (behavioral, commitment). The options in each subscale are assigned an ordinal value with a range from 1, having the lowest value, and 5, having the highest value. A higher score in a sub-category relates to greater attendance, participation, as well as cognitive/behavioral, acceptance/commitment in that identified area.

Psycho-Educational Theorists and Theories Informing Program Curriculum Development

Adult Learning Theory

Attachment Theory: attachment styles, attachment patterns, attachment orientations

Bateson’s Brief Therapy, Theory of Double Bind, Feedback Loop, and Abduction

Bloom’s Taxonomy

Bowen’s Theory on Differentiated Self, and Genograms

Circular Causality in Family Systems Theory

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Differentiated Learning

Erikson's Stages of Psychosocial Development

Interpersonal theory

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

Piaget's Stages of Cognitive Development

Positive Reinforcement and Operant Conditioning

Restorative Justice and Accountability Journaling

Scaffold Learning Theory

Van Der Kolk, MD, Trauma Informed Treatment

Trauma Informed Treatment with LGBTQIA Individuals and Community

References

Bloom, B. S. (1956). "Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive

Domain." New York: David McKay Co Inc.

Cho, C. K., & Cho, T. S. (2018). On Averting Negative Emotion: Remedying the Impact of

Shifting Expectations. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 2121. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02121

Healy, D., (2020). S2S Love and Compassion Cycle Diagram. Streets2Schools STC Approved

Professional Development Training; VSRS-Module-1. 4-hour training. 2020.

Healy, D. (2020). Whole-Souled Success Curriculum. Cedar Rose Publishing and Consulting.

Levy, E. (2007). Gradual Release of Responsibility: I do, We do, You do. Retrieved Ellen

Levy© E.L. Achieve/2007

Mason, M. (2021). The Cycle of Violence Wheel Image. Captured from the internet:

https://mmcenter.org/stay-informed/cycle-violence

Van de Pol, J., Volman, M., & Beishuizen, J. (2010). Scaffolding in teacher-student interaction:

A decade of research. Educational Psychology Review, 22, 271–297. doi:10.1007/s10648-010-9127-6.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem-solving. Journal of

Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 17, 89–100. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x.

Additional Contributing References

AB 372. (2018). Captured from internet: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov. Date Published:

09/07/2018 09:00 PM

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching.

Retrieved [2/28/22] from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.

Babcock, J. C., Green, C. E., & Robie, C. (2004). Does batterers’ treatment work? A meta

analytic review of domestic violence treatment. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 1023–1053. 10.1016/j.cpr.2002.07.001

Babcock, J., Armenti, N., Cannon, C., Lauve-Moon, K., Buttell, F., Ferreira, R., Solano, I.

(2016). Domestic violence perpetrator programs: A proposal for evidence-based standards in the United States. Partner Abuse, 7, 355–460. 10.1891/1946-6560.7.4.355

Belingheri P, Chiarello F, Fronzetti Colladon A, Rovelli P (2021) Twenty years of gender

equality research: A scoping review based on a new semantic indicator. PLoS ONE 16(9): e0256474. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256474

Bogenschneider, K., Little, O. M., Ooms, T., Benning, S., Cadigan, K., & Corbett, T. (2012).

The family impact lens: A family-focused, evidence-informed approach to policy and practice. Family Relations, 61(3), 514–531.

Cal. Fam. Code §§ 6218 & 6389. Captured from internet: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov.

Cal. Family Code §§ 6343. 1993. Captured from internet: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov.

1993, Ch. 219, Sec. 154

Cal. Penal Code § 18250. Cal. Penal Code § 27545. Captured from internet:

https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov.

Cal. Penal Code § 29805. 2010. Captured from internet: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov. 2010,

Ch. 711, Sec. 6

Cal. Penal Code §§ 26815(a). Captured from internet: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov.

Cal. Penal Code §§ 29810; Cal. Fam. Code §§ 6389. Captured from internet:

https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov.

California Code, Penal Code - PEN § 1203.097. Captured from the internet:

https://codes.findlaw.com/ca/penal-code/pen-sect-1203-097.html

California Code, Penal Code - PEN § 1203.098. Captured from the internet:

https://codes.findlaw.com/ca/penal-code/pen-sect-1203-098.html

Cotti, C., Foster, J., Haley, R., Rawski, S., (2020) Duluth versus cognitive behavioral therapy:

A natural field experiment on intimate partner violence diversion programs. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, Vol 26(2), Jun, 2020. pp. 384-395.

Cross, C. (2016). Reentering Survivors: Invisible at the Intersection of the Criminal Legal

System and the Domestic Violence Movement. Berkeley Journal of Gender, Law & Justice, 31(1), 60–120.

Eckhardt, C. I., Murphy, C. M., Whitaker, D. J., Sprunger, J., Dykstra, R., & Woodard, K.

(2013). The effectiveness of intervention programs for perpetrators and victims of intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 4, 196–231. 10.1891/1946-6560.4.2.196

Fernández-Fernández, R., Navas, M. P., & Sobral, J. (2022). What is Known about the

Intervention with Gender Abusers? A Meta-analysis on Intervention Effectiveness. Anuario de Psicologia Juridica, 32(1), 23–31. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2021a17

Hirji, S. (2021). Oppressive Double Binds. Ethics, 131(4), 643–669.

https://doi.org/10.1086/713943

Lorenzetti, Liza & Wells, Lana & Logie, Carmen & Callaghan, Tonya. (2017). Understanding

and preventing domestic violence in the lives of gender and sexually diverse persons. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 26. 175-185. 10.3138/cjhs.2016-0007.

MacLeod, D., Pi, R., Smith, D., Rose- Goodwin, L. (2009) Batterer Intervention Systems in

California: An Evaluation. California Adminstrative Office of the Courts, Office of Court Research.

NCADV, National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, 2010 Summary Report,

captured from online at: https://ncadv.org/STATISTICS

NCADV. 2020. Captured from internet: https://ncadv.org/state-by-state

Pence, E., & Paymar, M. (1993). Education groups for men who batter: The Duluth Model. New York, NY: Springer.

O’Connell, K., Wilson, M. Lead Project Consultants (2022) AB 372 Legislative Report: Year 1

Applying Evidence Based Practices to Batterers Intervention Programs. Support Hub for Criminal Justice Programming. California State Association of Counties

Zarlin, A., Bannon, S., Berta, M., (2019) Evaluation of acceptance and commitment therapy for

domestic violence offenders. Psychology of Violence, Vol 9(3), May, 2019. pp. 257-266.

Zarling, A., Lawrence, E., & Marchman, J. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of acceptance

and commitment therapy for aggressive behavior. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 83(1), 199.

Copyright © 2022 Streets2Schools, Inc

All rights reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without expressed permission in writing except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review and properly reference the source.